The October 2022 report from the UK’s Environment and Climate Change Committee, In our hands: behaviour change for climate and environmental goals, states that one third of greenhouse gas emissions reductions up to 2035 require decisions by individuals and households. The report says that without behaviour change it will be impossible to meet the UK’s 2050 net-zero target. (The report does not question whether targets based on IPCC projections are adequate for tackling the climate emergency.)

Something similar could be assumed for countries like Australia, Canada, and the US, or perhaps behaviour change is even more essential since their current per capita emissions are roughly double those of the UK.

The above graph showing Google search trends for the year to April 2023 suggests quite a high interest in climate action, but what type of action? Are people searching for information on how to change their own behaviour? Or are they hoping the big climate-related actions only governments can make will be sufficient?

Certainly per capita emissions will fall regardless of behaviour change if and when governments take the necessary actions for enabling use of renewable energy for everything, but even if governments operate in true emergency mode that will take time…and we don’t have time. Perhaps that’s why the above report identifies ‘up to 2035’ as a key period.

Who should change their behaviour?

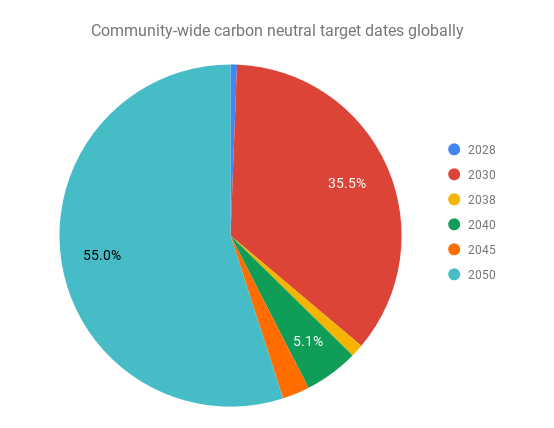

The following chart is based around the overly-conservative IPCC projections. Really we need ‘as much as possible as quickly as possible’, preferably by yesterday. But despite being overly rosy, the chart paints a daunting picture of the scope of change that the UK report says is required, particularly in rich nations.

A recent Guardian article makes the point that “nearly half the world’s carbon emissions are caused by the world’s richest 10% of people, and nearly two-thirds of Australian adults fall inside that 10%”. Further, it states that the poorest 50% of the world’s population averages 1.4t per person per year. (Mine is about double that despite having solar on the roof of my all-electric house, not having a car, and rarely buying anything other than food.)

A University of NSW study showed that the average Potts Point resident could reduce their footprint by 60% simply by living like someone 25km to the west in Auburn. Relatively rich people can afford to reduce their emissions via energy efficiency upgrades and fuel switching, but their biggest capacity to reduce carbon emissions is simply to consume a lot less. Ironically, the bigger our current carbon footprint the more scope we have for achieving climate benefit by changing our behaviour.

Are education and incentives enough?

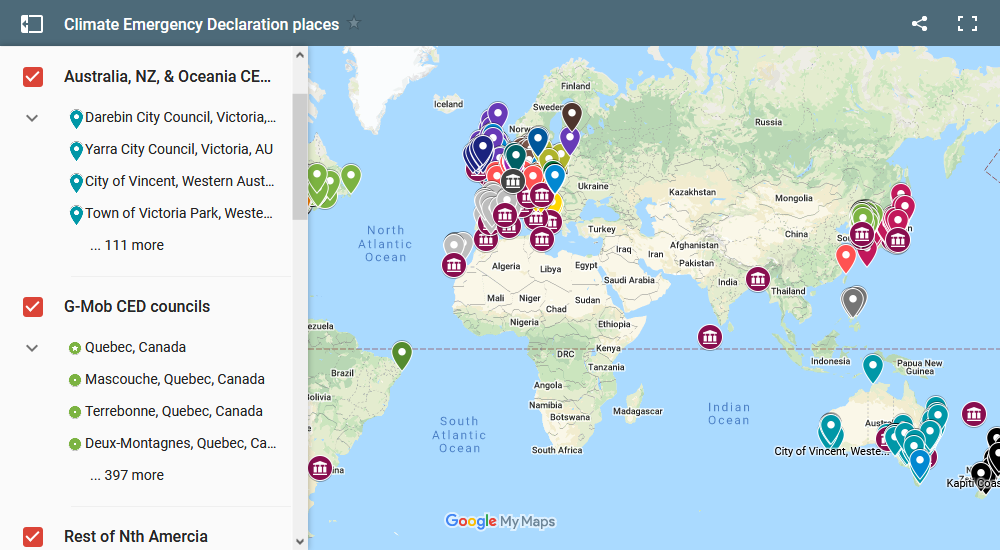

Local councils that have passed a Climate Emergency Declaration (CED) rely heavily on education and incentives to encourage voluntary behaviour change. By way of recent examples, Cambridge City Council is providing funding to Cambridge Carbon Footprint to host free climate change training sessions for residents to help them make positive changes. Darwin City Council is providing grants of between $5,000 and $50,000 for community projects that advance the aims designated in their Climate Emergency Strategy.

A large percentage of CED councils have climate education website pages that encourage behaviour change, and some also offer incentives. You can see a random selection of examples here. But how many residents see those pages? And even if they do, how many residents will feel sufficiently motivated to make more than the minor or easiest voluntary behaviour changes?

The tone of such pages is generally just gentle encouragement, with little sense that big changes in behaviour are necessary. Recently though I’ve seen a couple of cases of UK CED councils, including Cambridge, encouraging residents to use carbon footprint calculators to measure (and reduce) their own climate impact. Another, Gateshead Council, is encouraging local residents and businesses to make climate pledges.

Mandatory behaviour change

The UK report on behaviour change mentions regulation as a third means of achieving change, alongside education and incentives. However, local councils have much less scope than national and state governments for introducing climate-focused regulations.

The European Investment Bank’s (EIB) climate survey for 2022-2023 reports that two-thirds of the people in Europe (66%) support stricter government measures to change people’s individual behaviour to tackle climate change. 56% say they support a carbon budget system that would allocate each individual a fixed number of yearly credits to be spent on items with a big carbon footprint (non-essential goods, flights, meat, etc.)

One of the big obstacles to achieving voluntary behaviour change is a sense that change by one person won’t make much difference. Even if someone is well aware of the carbon footprint of flying, for example, it can seem pointless to miss out on things that require taking a flight if one sees everyone else flying just as much as ever.

However, if there were mandatory limits on flight miles, or even an almost total ban, everyone would be in the same boat. It would be fair, and we’d know that the change in behaviour is making a difference. I guess nobody really liked rationing during WWII, but it was generally accepted as being fair and effective.

In addition, regulations and bans have educational benefit. Who stopped to think that there might be more efficient lighting options until the sale of incandescent light bulbs was banned? Once upon a time gas appliances were generally considered to be a good choice, but proposals for (and controversy over) local bans on gas connections to new buildings raise awareness about why that is no longer so.

Local council regulations

Local councils might not have a lot of scope to make climate-related regulations themselves, but it seems highly unlikely that voluntary behaviour change will be enough. Councils could lobby national and state governments for climate-related regulations or bans for things beyond council control.

But what climate-related regulations might be possible for local councils? Some French councils have banned outdoor heating at cafes and bars. Some US councils have banned gas use in new buildings or new gasoline stations for refuelling conventional vehicles. Some UK councils have banned car idling outside schools when parents wait to pick up their children.

Eleven Australian local councils have banned advertising of carbon-intensive products in council-controlled areas. The Climate Emergency UK council scorecards includes the question, Has the council passed a motion to ban high carbon advertising and sponsorship?, as one of their scored action items.

If local councils can introduce some regulations or bans, even if minor ones, it sends a message to the wider community that the council recognises that behaviour change is essential.

And finally…an update!

At the third(?) attempt, the South Australian Local Government Association (LGA), the peak body for local councils in SA, this week declared a Climate and Biodiversity Emergency. The motion read:

Part 1: That the LGA recognise the climate crisis; and

Part 2: That the LGA declare a Climate & Biodiversity Emergency.

This follows on from climate emergency declarations by the SA state government and 16 local councils in SA. In earlier years there have also been Climate Emergency motions by the state LGAs of Victoria (May 2017), WA (May 2018), and NSW (Oct 2019) and by the national LGA peak body (June 2019). Those motions can be seen here.

If you’d like to receive future cedamia blog articles about new CEDs and council post-CED actions (one or two a month) directly to your inbox, click the Follow button below and set how you prefer to receive them.